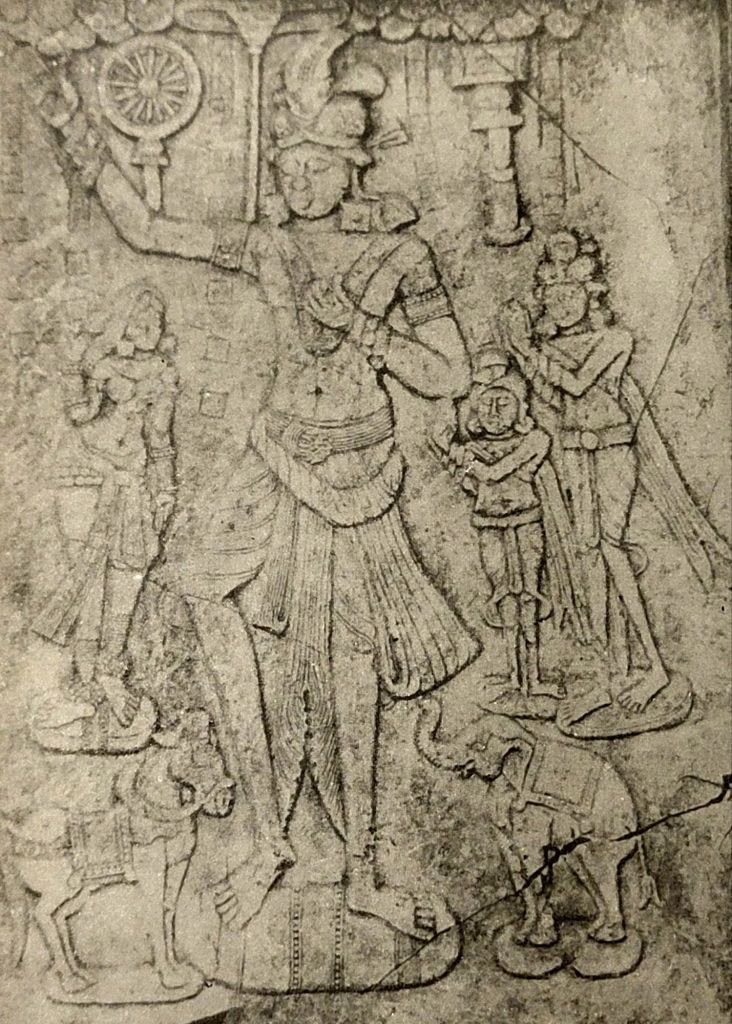

Fig 1. The Circulation of the Shower of Wealth: a Caktavartin with the umbrella of Dominion and the Seven Treasures. Jagayyapeta, 2nd century B.C. (After Coomaraswamy)

I have been slow to begin my series on Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy’s Spiritual Authority and Temporal Power in the Indian Theory of Government,1 but here is the first installment. It is, arguably, the most complex and integrative of Coomaraswamy’s three most profound texts, the other two being Hinduism and Buddhism and Time and Eternity. I have been reading and rereading Time and Eternity slowly for the best part of 25 years but have only recently begun studying Hinduism and Buddhism and Spiritual Authority and Temporal Power in the Indian Theory of Government. It has not been easy work without proficiency in Sanskrit, Latin and a host of other languages that would render a comprehension of Coomaraswamy’s uncompromising work more complete. Nevertheless, I have taken it upon myself to attempt this task, and share my reflections on this text, as limited as they might be. I am particularly interested in understanding contemporary governance in its light.

I will begin with six contextualizing themes: 1) Post traditionalism, 2) the relationship of Traditionalism with Fascism, 3) the precedence of Rene Guenon’s Spiritual Authority and Temporal Power,2 4) the implied validation of varna or the caste system, 5) the implied gender hierarchy, and 6) the image of the Cakravartin. In this, the first post in the series, I will deal with the image of the Cakravartin, which, as the frontispiece, is quite literally, the opening of the book. This image is captioned, “The Circulation of the Shower of Wealth: a Cakravartin with the umbrella of Dominion and the Seven Treasures. Jagayyapeta, 2nd century B.C.”

The Cakravartin expresses the Indic ideal of the Universal Monarch and was developed as an icon in the Andhra region during the Buddhist era. The concept was defined and perpetuated in the Brahmanical Kautilya Arthasastra. As John M. Rosenfield notes in The Dynastic Arts of the Kushans, “In the relief carvings of Amaravati and Nagarjunikonda the Cakravartin is usually shown surrounded by the seven emblems of his supremacy: the great discus of unimpeded conquest [cakra], the state elephant on which the king can ride to the very ends of the earth and back in one day, his equally remarkable charger, the octagonal gem which is so luminous that it can light the path of his army by night, the all-wise finance minister, the beautiful consort who is the very embodiment of his prosperity, and his prime minister (or the crown prince). These seven attributes of his dignity, the sapta ratna, come supernaturally to the king when he has attained a requisite degree of virtue.”3 The number and variety of the “jewels” or ratnas varies, sometimes including householder, general, and chariot, with the source being referred to, but there are usually seven and the symbolism is consistent.

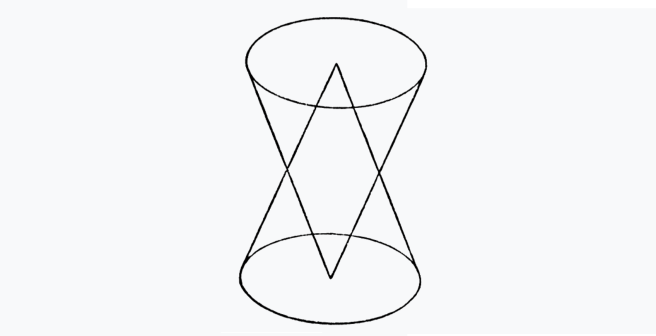

As Coomaraswamy notes, according to traditional doctrine, not just Indian but universal doctrine, the life and fertility of the realm depends upon the King.4 If the King fails to fulfil his duty, by way of ritual and metaphysical sacrifice, the wealth and bounty that falls from the sky as rain will cease. This is what the Cakravartin icon symbolizes. The image ties the actions of the King to the fate of the land in a perpetual circulation of gifts – the Gods confer their bounty and the King presents his sacrifice. Coomaraswamy translates and interprets verses from the Satapatha Brahmana on the relationship between the Shower of Wealth and the Cakravartin thus, “its [the Shower of Wealth] self or body (atman) is the sky, the cloud its udder, lightning its teat, the shower the shower (the rain); from the sky it comes to the cow (i.e. from the Sky as archetypal cow to the earthly cow … ), its self or body is the cow … its shower the shower (of milk); and from the cow it comes to the Sacrificer. He [the Cakravartin] (in turn) is the self or the body, his arm its udder, the offering ladle its teat, the shower the shower (of ghi). From the Sacrificer to the Gods: from the Gods to the Cow; from the cow to the Sacrificer; thus circulates this perpetual neverending food of the Gods.” 5

Coomaraswamy specifically addresses the Cakravartin as represented in sculptural reliefs. in Amaravati (similar to the frontispiece which is from Jagayyapeta) He explains that the image shows the Cakravartin raising his right hand up to the clouds (signifying his sacrifice), and that from the sky, a shower of coins is falling (signifying the bounty).6 The image, as a whole, signifies the circulation of wealth, produced and perpetuated by the ritual (outward) and metaphysical (inward) righteousness of the Universal Monarch – the Cakravartin.

- Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, Spiritual Authority and Temporal Power in the Indian Theory of Government (Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 1978),

- Rene Guenon, Spiritual Authority and Temporal Power (Sophia Perennis, 2001).

- John M. Rosenfield, The Dynastic Arts of the Kushans (University of California Press, 1967), 175.

- Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, Spiritual Authority, 68.

- Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, Spiritual Authority, 68.

- Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, Spiritual Authority, 69.

You must be logged in to post a comment.